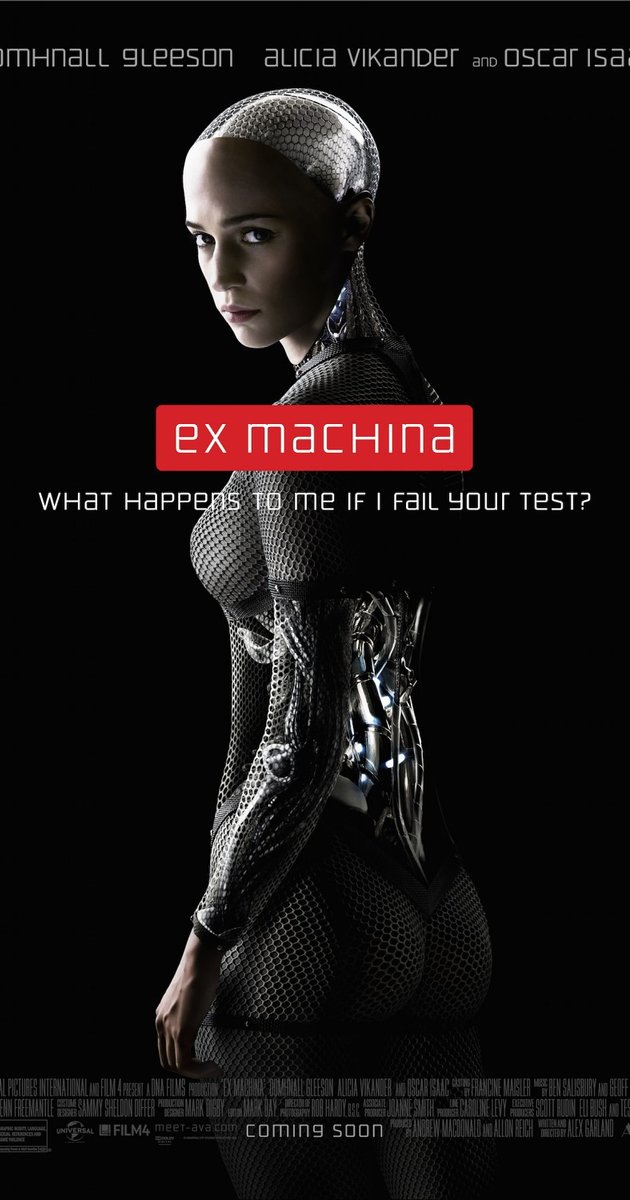

A Review of 'Ex Machina'

(Movie released April 10, 2015)

by R. Greg Grooms

“To be or not to be- that is the question.” Hamlet, Act III, Scene 1

Things were changing when Mortimer Adler published his The DIfference of Man and the Difference It Makes in 1966. The centuries-old belief that there is something unique and universal about being human was under attack. To determinists like B.F. Skinner being human was simply a matter of biology, one that isn’t so unique after all. Post-moderns like Michel Foucault saw human nature as an ever-changing picture painted by social forces, especially language.

The shifting philosophical sands between Adler, Skinner, and Foucault proved to be fertile ground for the arts. In the decades that followed Adler’s book lots of films nibbled away at his argument. For example, 2001: A Space Odyssey wondered aloud if computers could be intelligent, too. Built upon an assumption of naturalism, its logic was unassailable: mechanical forces produce intelligence in us, ergo they can do so in machines. To illustrate this 2001 gave us HAL, a computer that was not only intelligent, but psychotic, too.

Ex Machina’s Ava (Alicia Vikander) is the answer to a very different question.

But before we meet her, director Alex Garland introduces us to Caleb (Domnall Gleeson). Think of him as Everyman of the Computer Age. We meet him in a cubicle, working on a computer as a software engineer in the world’s largest internet company. His isn’t the most exciting life in the world, but as we meet him, he gets exciting news: he’s won the company lottery and first prize is a week with the company’s reclusive head, founder and resident genius, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), in his remote fastness in Norway. Before he/we know it, he’s whisked away by helicopter and introduced to Nathan, who explains why he’s here.

It’s simple: Nathan has invented artificial intelligence and Caleb is to be its Turing test. Named after Alan Turing (of The Imitation Game) the test is designed to determine if a computer is intelligent. From the start Nathan goes out of his way to tickle Caleb’s ego. It seems he wasn’t randomly selected after all.

Caleb: Why me?

Nathan: I needed someone that would ask the right questions, so I did a search and I found the most talented coder in my company. You know, instead of seeing this as a deception, you should see it as proof.

Caleb: Proof of what?

Nathan: Come on, Caleb. You don't think I don't know what it's like to be smart? Smarter than everyone else. Jockeying for position. You got the light on you, man. Not lucky. Chosen.

Then he introduces him to Ava. Three things are evident about her. First, she is a machine. Her face, hands, and feet look human down to the very skin that covers them, but her mechanical arms and legs are transparent. We not only see her gears and wires, we hear them faintly when she moves. Second, she is undoubtedly intelligent, even more so than Caleb. Third, she is very beautiful. When Caleb asks Nathan why he made her so, he offers this explanation: we have no experience of personality that is not gender-based, so creating artificial intelligence that is neither male nor female is just too hard. Caleb’s counter suggestion proves to be more to the point. Is she beautiful, he wonders, for the same reason the magician’s assistant is beautiful, i.e., to distract the audience from what really going on?

What’s really going on becomes clear only slowly. From the start Caleb and Ava are only allowed to interact through a glass wall, never truly face to face. We learn that Ava is a prisoner, locked in and perpetually under surveillance. So too, Caleb finds, is he. His comings and goings are carefully restricted by Nathan’s high-tech security system. What at first looks merely awkward soon becomes sinister, when Ava warns Caleb that all is not as it seems and Nathan is not to be trusted.

As we get to know Nathan, he certainly feels less than trustworthy. He’s easy not to like, not to trust. He’s brilliant to be sure, but also arrogant, crass, unashamedly self-centered and inclined to drink too much. His conversations with Caleb range over a wide variety of fascinating subjects: God, creation, love, sex, etc. but his comments never rise above the level of a junior high boy in a locker room. He’s abusive to Kyoko, an earlier, less-advanced model of Ava. And dear, sweet beautiful Ava is everything Nathan isn’t. So, when she suggests escape to Caleb, he willingly assists her in concocting a plan.

All comes to a head the night before Caleb’s scheduled departure. At their farewell dinner, Nathan gets a little drunk and tells Caleb what’s really been going on: Ava isn’t the test subject. He is. Her challenge isn’t to persuade him that she’s intelligent, it’s to gain his trust, deceive him, and use him to escape for this in Nathan’s opinion is the true test: a real self is one that can be selfish, can use others for its own ends.

Ex Machina’s conclusion is predictably violent. Let me warn you of it and leave it to your imagination.

It’s tempting to see this fable as a fulfillment of Stephen Hawking’s prophecy to the BBC in December of 2014: “The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race." He fears the Terminator series run amok. If machines become smarter and more powerful than us, we’re doomed to lose Darwin’s survival of the fittest game. But seeing Garland’s film in that light, I think, would be foolish and self-serving, for as he made clear in an NPR interview in April of 2015 the problem he’s warning us of isn’t Ava, it’s us: “The tension in this film is much more directed at the humans.”

I’m reminded of the words of Lewis’ Screwtape here:

“The whole philosophy of Hell rests on recognition of the axiom that one thing is not another thing, and, specially, that one self is not another self. My good is my good and your good is yours. What one gains another loses. Even an inanimate object is what it is by excluding all other objects from the space it occupies; if it expands, it does so by thrusting other objects aside or by absorbing them. A self does the same. With beasts the absorption takes the form of eating; for us, it means the sucking of will and freedom out of a weaker self into a stronger. “To be” means “to be in competition”.

I heartily recommend Ex Machina to you.